John Dugdale Interview

Oct 6, 2014 / Photography / Influences / interview

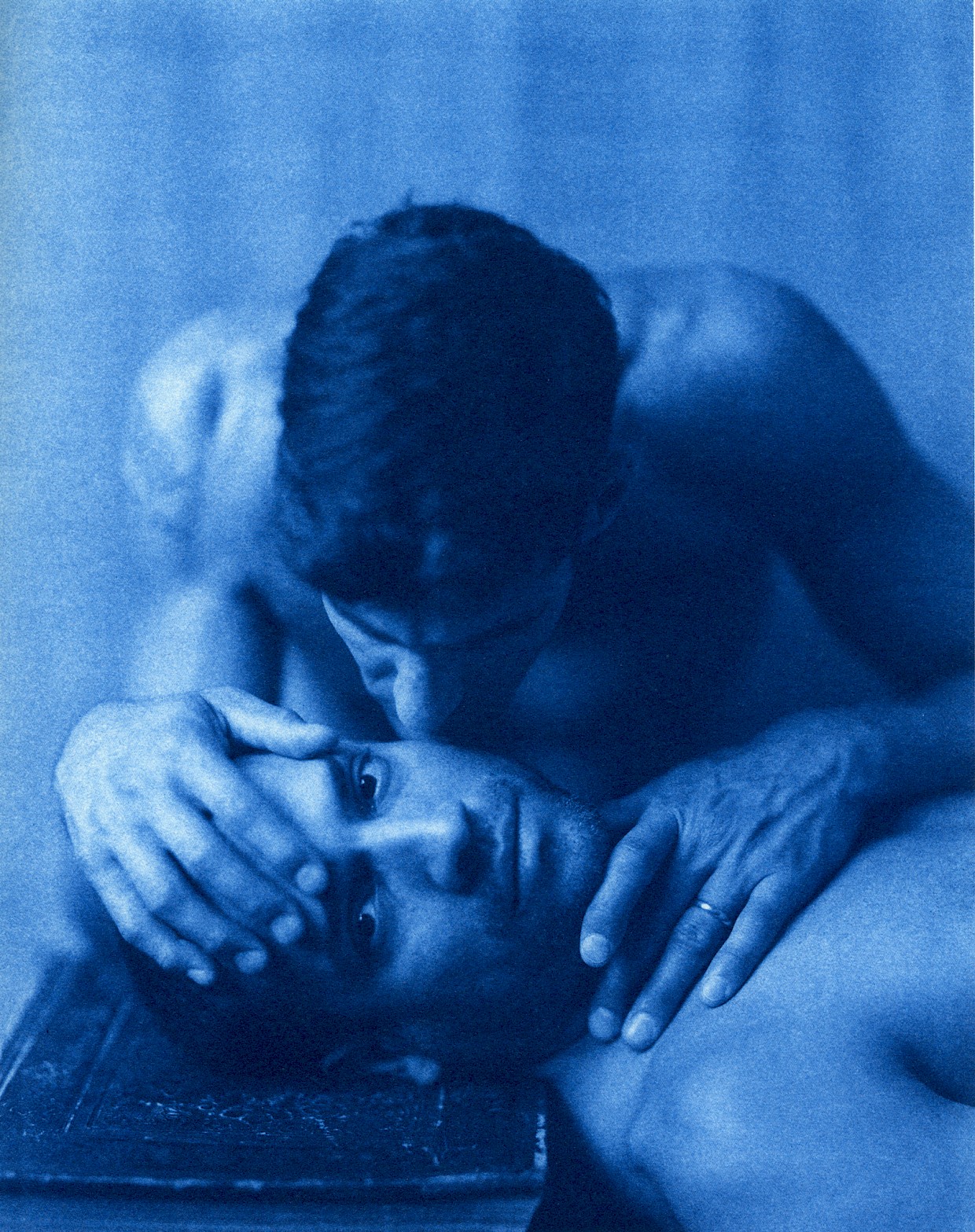

Following Jeff Koon’s article last week, I remembered an interview that I did in 2010 with John Dugdale for an MFA assignment. John Dugdale is a huge influence. He was the catalyst for me trying out cyanotype, the 19th-century printing process that produces a blue print.

Reading this interview now (four years later) makes me realize that even then, I was curious about the same things: how artists create, where ideas come from, and how do we become the people we want to be.

I recently reconnected with John and asked for his permission to publish this interview. He agreed. Hopefully this interview will inspire someone as much as it inspired me.

John Dugdale

John Dugdale was born in Stamford, Connecticut on June 2, 1960. He was 12 when his mother gave him his first camera. On a lark, he signed up for a grade 10 photography class.

Throughout his teens, he was already paying his dues and honing his photographic style. By the time he attended the School of Visual Arts in New York City in 1980 to 1984, he already had a strong sense of who he was as a photographer. From there, he became a commercial photographer shooting for catalogs and advertising.

John’s immune system started to fail in 1993 when he discovered that he had CMV retinitis condition that usually occurs in the late stages of AIDS and causes blindness. He became fully blind in his right eye, and his left has about 20% vision left. It was 1993, and there were no medical treatments at that time that could manage AIDS. He was 33 years old.

Seventeen years later, numerous shows and an international reputation for making moving and haunting images on historical processes such as cyanotypes, John Dugdale is optimistic and working.

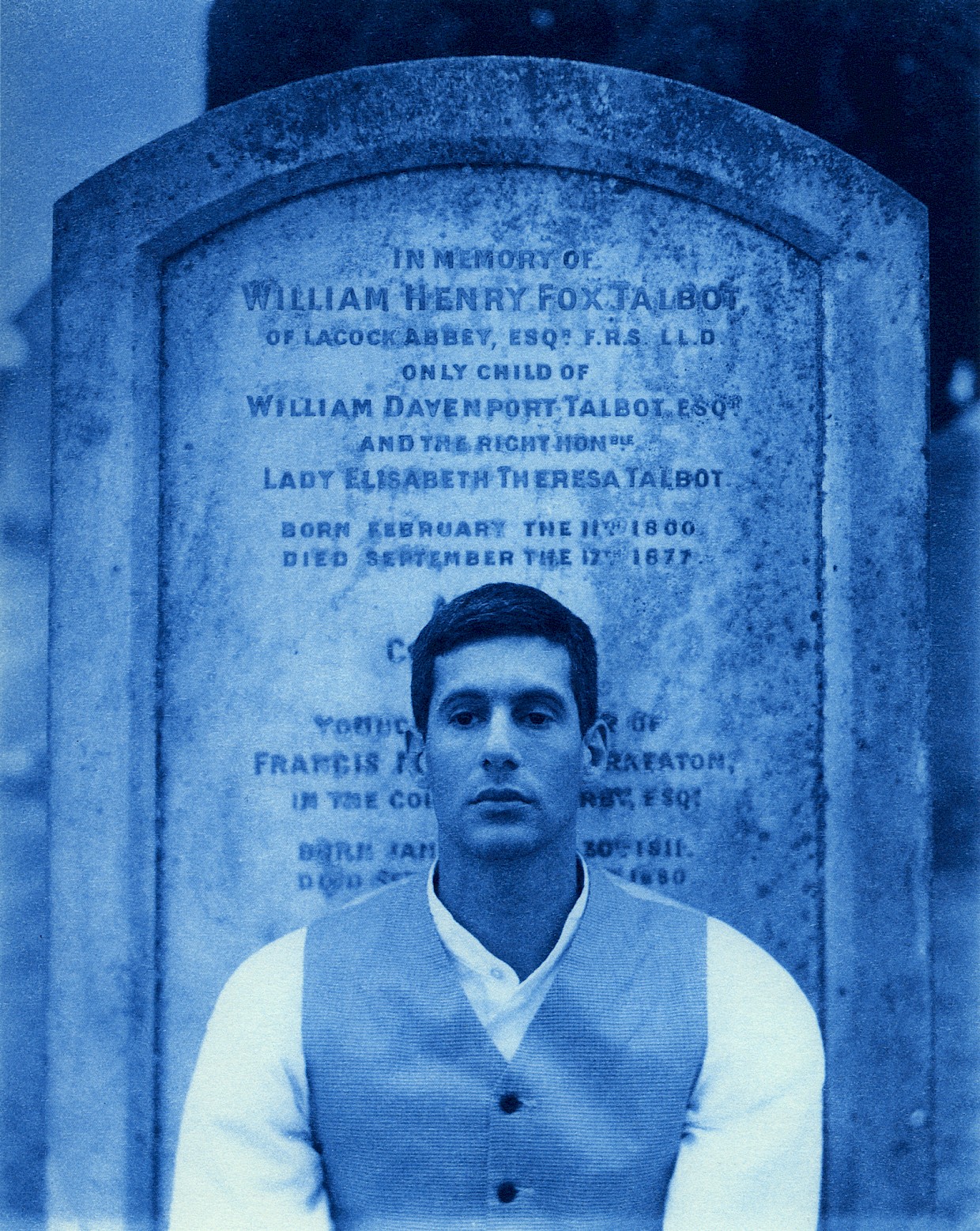

John counts among his influences Alfred Stieglitz, Julia Margaret Cameron, and William Henry Fox Talbot. He uses antique large-format cameras (he’s got three now). In John’s website, he mentions “the quietude that people respond to in my pictures is, in part, because of the way the pictures are made: no flash; no harsh electric light; not even the sound of the shutter–just a lens cap removed, and then gently replaced. This encounter provides, for me, a metaphor for looking. My visual impairment allows me to provide a meditation upon the experiences of vision: visual loss is, after all, a visual experience.”

My interview with John primarily focused on his creative approach. I include the most important excerpts below.

Creative Approach

John does not photograph every day. He reads and thinks about titles for images. He creates about 200 images every couple of months. Of that, he nurtures about 20-25 images. He takes the working book of pictures that he has created and shows the images to people he trusts. He observes which images people spend the most time on, which images people react to the most.

When you start to create a photograph. Do you have any rituals?

If I think of a ritual it would be during the actual moment of opening and closing the shutter, it almost seems mystical to me. I don’t really prepare for it. When I step into the light or in front of the window, that’s when something extremely mysterious happens for me, I feel like I can see the photograph. If you spoke to any number of blind people, they will tell you that you could see very clearly in your mind. I just happen to have a large pictorial rolodex in my head, a whole big giant list of pictures that I’ve seen in my life that I call on.

But before you step into the light, you’ve already thought about what the picture will look like. It’s not like you’re experimenting.

No, not at all. I did that during my commercial life when I jumped all over the place trying to get foxy angles, from every angle and jumping them around doing these fashion things, which I never meant to do, and I would think “this is not what Stieglitz did.” I had two ideas over the weekend, both from a book that I was reading, and instantaneously, the pictures existed in my mind. They just appear full blown, there might be a tiny bit of adjusting to make it work, but they already perfectly exist in my mind. This sounds kind of hokey, but that’s exactly what happens. When I hear a word or a series of words, it creates a picture. That’s where the notes come in, I have a giant marker and a pad and scribble down the phrase because it’s inevitable that it will slip my mind if I’m reading at night. It really has worked beautifully for me.

Do you do journaling? I read that you sketch and title each image before it is made. Actually that’s what you said, you already thought about what the title is.

I had a huge experience with HIV and I had something rare and I had a stroke. While I wasn’t able to draw at that time, I just spoke photographs into a little tape recorder. As I regained use of my hands, I started making stick figure sketches.

Do you do that now?

I don’t need to do that now. Having a title is enough. I’ll give an example from these last couple of days. I’m reading a book about the origins of the GospelsäóîMatthew, Mark, Luke, and John. There’s this beautiful phrase I’ve heard over and over again, and it comes up all the time during Lent and Easter, there’s a line where someone says, äóìwomen of Jerusalem, why do you weep?äóù and in that instant when I read it again this time, because I had my head bowed down while my eye is healing [John recently had eye surgery], I saw in my mind, six men sitting in a semi-circle of chairs with their heads bowed down with their backs to the camera and a large sky up above them. And I would put the title “Women of Jerusalem, Why Do You Weep?” and then you put that out into the world, and the shocking thing is how people respond to that from their own personal history. I won’t say that I made this picture because my head has to be a certain way while my retina is healing. I’ll just let it out into the universe and see how people respond from their person. It’s inevitable that what activates an image of any kind, a painting, a sculpture, a photograph, is what people bring to it their personal history.

So when you show one of your photographs, do you explain what the concept is?

Only rarely. When I’m in a class situation I think it’s helpful, people like to understand the process. I wrote a book of 40 essays that poetically describe the source of each of those 40 photographs on my 40th birthday. Life’s Evening Hour, that book.

Yes, I have that actually, I bought it. I love it.

Excellent, thank you. That’s a good example of what I might want to say about the photographs. It never goes to the focal lengths, it’s nothing about the science of it, it’s really about the spirit of it. [and the feeling] Yes, that’s right, feeling is spirit.

You want to talk about spirit, my heroine, Julia Margaret Cameron, is a perfect example. She kicked the tripod sometimes on purpose to get the effect that she wanted. If a piece of glass plate broke in half she still printed it, and then men in England at that time who were in charge of the photographic world derided her and said she was foolish and didn’t know what she was doing. My theory is that she knew exactly what she was doing. Her work has such incredible power over everyone because it came from her heart, it came from her family, it came from the people who she loved. She was a real artist with the camera. She was pretty dedicated to dragging people into her studio.

Yeah, She was controlling in a way, I’ve read that.

Yes, yes. I think she was a little crazy, but I think that’s suitable. You have to be a little nuts.

Are you like that though?

Yes, you have to be a little nuts in the world to make your life be what you want it to be. You can’t follow any rules, within reason. If you’re going to follow along with everybody else and not follow your inspiration then you’re going to fall by the wayside. You know, answering the question what is my suggestion for people starting out, there is nothing more important than following that spirit especially when it doesn’t make any sense because eventually it will. The world will come to you. It’s very interesting sometimes to look back at early pictures of mine because I could see the seeds of the pure quietness of it now that was just starting there. This does not have to happen, but I ended having to lose my sight, to get the clarity that I wanted which is a shocking thing for people to hear but it’s really true. It enabled me to be so quiet. What I thought was going to be a limitation, turned out to be my style.

* * *

Emerging artists inevitably compare their own work at their stage to well established artists like you and they conclude that they are not talented, they don’t have what it takes. I wanted to ask a couple of questions surrounding this idea. When you have an idea, you have a title, and you go and shoot it, but it’s not working, do you give up?

I move on. If you have to belabor something then it’s not going to be successful. You can’t be grinding your teeth, pulling your hair, trying to make something work when it’s not going to work. I learned that in my commercial life. If it’s not working, move on to the next thing.

But when do you make this decision?

That’s the magical moment, you’ll know in your mind. I’m looking forward to being with my students. It’s a small class: two cameras, two backdrops, and three people per camera. I think what I can teach well now is composition and when to stop and when to go forward. There’s a minute difference sometimes between objects being on the perfect spot or not. It could the difference of a 1mm shift of an object. It’s just talent, and you could hone that talent by practicing. I got to practice by doing hundreds of catalogs. I had to show two shoes in a creative way, a wedding dress, or a pile of carrots. I did all that. I didn’t love what I was doing, but it made good work, and I didn’t realize that later on that that experience would really enable me to say, “no, you know this is not working.”

What is your success rate when you create photographs? How many do you create and what ends up being shown?

Oh I would say if I take 10 sheets of film, it’s usually three, at first, will rise to the surface. And then I’ll letter them A, B, C, D, E, F, G, and H. There’s almost always one that rises up out of each batch that’s appropriate to print. And they get edited again after they are printed and I’ll show them to different people. There always one that sings out. It’s nice to shoot a small amount of film in a large camera because you really have to stop and think what you’re doing. In the beginning, I shot 100s of sheets of film because I didn’t know what I was doing, but eventually if you’re forced to make decisions during each composition, you’ll end up with something really beautiful quality work. A student came once, he wanted to show me his book, and he showed me a still life, and I said “how many pictures did you take to create this still life?” and he had taken 85 shots with his digital camera from every angle and he walked around in circles. I said “boy if you were my student, I would take that camera away from you and make you just take three pictures during the course of a week. You are not really making a composition if you are creating 85 angles and choosing one.”

It’s a different use, but I always think of Bresson’s “decisive moment.” You have to “make” that when you’re working a large camera. That moment is what creates your artistry. It’s not about photographing seven billion things because film for a digital camera is free and you can erase it. I think that’s a tragedy.

Wouldn’t you have walked through all the angles in your head just like the guy did with his camera?

No. no. I don’t walk through the angles in my head. It just appears as an image. Sometimes instead of being a photographer I feel like a projector, like the images come out of me fully blown. There’s no muddling around as to which is the right angle. It just either is or isn’t. Just like in “Women of Jerusalem Weeping” there’s just have to be six men in six chairs, there’s no doubt in my mind about that. And if we get there and it doesn’t work, then it doesn’t work.

I love this analogy of you being a projector. Does that mean then, that you say to people that the images don’t come from you, it comes from your Muse or from the universe?

I feel safe to tell you that I feel sometimes that I channel them because if you had told me when I had my full sight until I was 33 that I was going to be making the most important work of my life without my sight, I would never have believed it. I often feel like they made themselves, like I just allowed myself the openness to let them come right through me. Again not trying to be dramatic or corny, but I really don’t have a complete explanation of where they came from, because they poured out of me like a vessel.

I subscribe to that perspective as well. Some people just look at you and I just stop talking about it.

Just stay with your ideas because those people really don’t have an idea in their heads so they can’t understand you. I don’t mean that as a mean thing. I’ve taught classes all around the world and given lectures and talks and my favorite part is to answer questions afterwards and inevitably there’s always a young person and an older person who will say äóìI don’t know what to photographäóù and then I ask if they would just describe any event in their life and then turn that moment into a photograph for them and they’re like “oh.” I say what cataclysmic thing are you looking for that’s going to make this picture for you. How could you say you have nothing to photograph.

I really think that photographs have to have a personal thing in there.

Definitely. There is nothing wrong with imitating everything at first. No matter how hard you try to imitate a Fox Talbot or a Cameron or anything like that that you love, doesn’t matter who it is, you can’t help but get your personal invested in it. There is no way to copy something perfectly.

I’m copying you for my final assignment in this class.

Excellent. Which one are you copying?

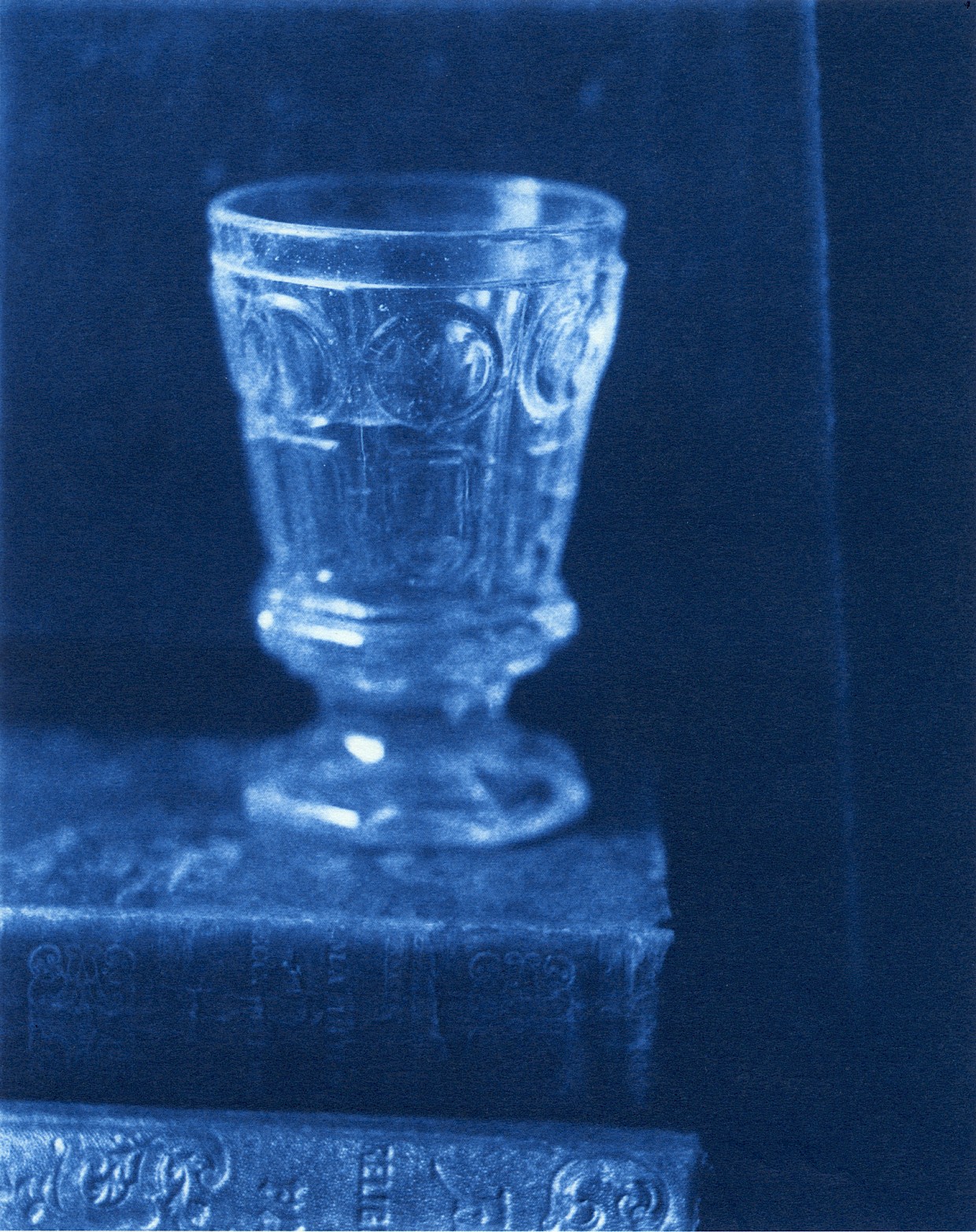

I love the Luminous Glass.

Oh beautiful. That was the last picture that I focused by myself as my sight was diminishing. It took me four hours to focus it. I just agonized focusing that perfectly until I felt it was perfect. I stopped down the lens a little and took that picture and I felt satisfied that I didn’t have to prove anything to anyone anymore that I could focus. I just let go of that so I could take more pictures. I love that picture.